Okay, so, "level-design-based dungeon generation"?

I’ve seen quite a few dungeon generators, but in the vast majority, they all boil down to “it’s a bunch of rooms connected with corridors”, or, “it’s a maze of rooms after rooms, some are interconnected”. And honestly, while some end up looking realistic, as far as I could tell, they all ignore the basic rules of level designing.

In this first part, we will be focusing on the theory and the general structure, then we will tackle the geometry later.

This is important, as it is the main gripe I have against standard generators!

Most generators will generate the rooms first, then only afterwards decide to fill them in with obstacles and rewards. That is not how you normally design a level. I mean, I guess you could do that, but unless you have a clear idea of the entire dungeon’s structure, that’s a recipe for disaster. So what you want to do is to first think about the structure; that is to say, the order of events in your dungeon. Once that is decided, then you can create the rooms around that.

Think of it as if you were packing for moving out. You have a lot of stuff to move (your dungeon’s content), and you have to get cardboard boxes to put that stuff in (the dungeon’s room). You could just buy boxes at random, but then you’d have no way to efficiently categorize your stuff; inevitably, you’ll end up storing some of your clothes into your video-game’s box because of a lack of space, or you’ll have a huge box for your 3 single figmas and it’s just gonna be a mess to go through (dungeon exploring). Now instead, what you could do is to assess your possessions early, then buy boxes according to the space you’ll need. While it is a bit pricier, it looks a lot better and makes it much easier to go through.

Still here? Good. Let’s start.

Design rules

Main path

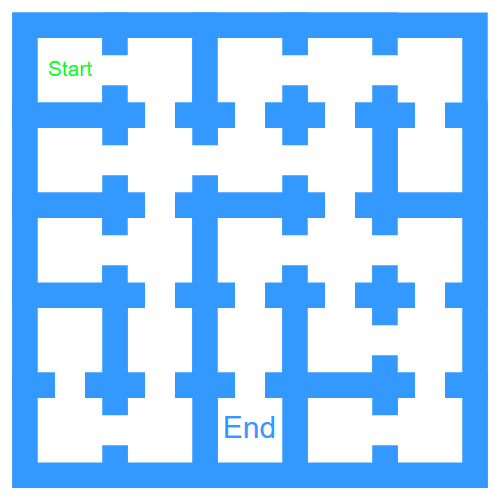

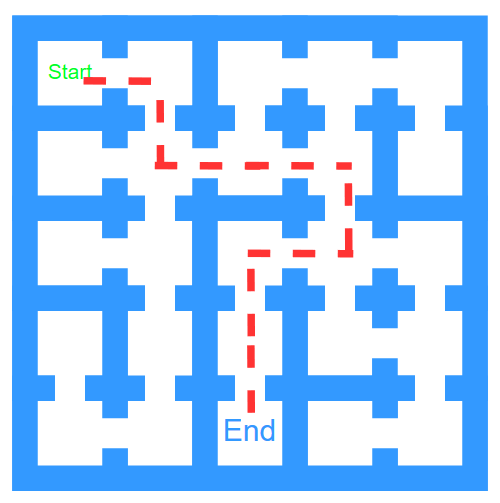

To start with, we’ll decide that a dungeon starts with a Starting Room, and ends with an Ending Room. There are at least one room in-between. For all intents and purposes, corridors will be considered as rooms, which, really, they are. They’re just long rooms and no I’ll take no criticism on that one.

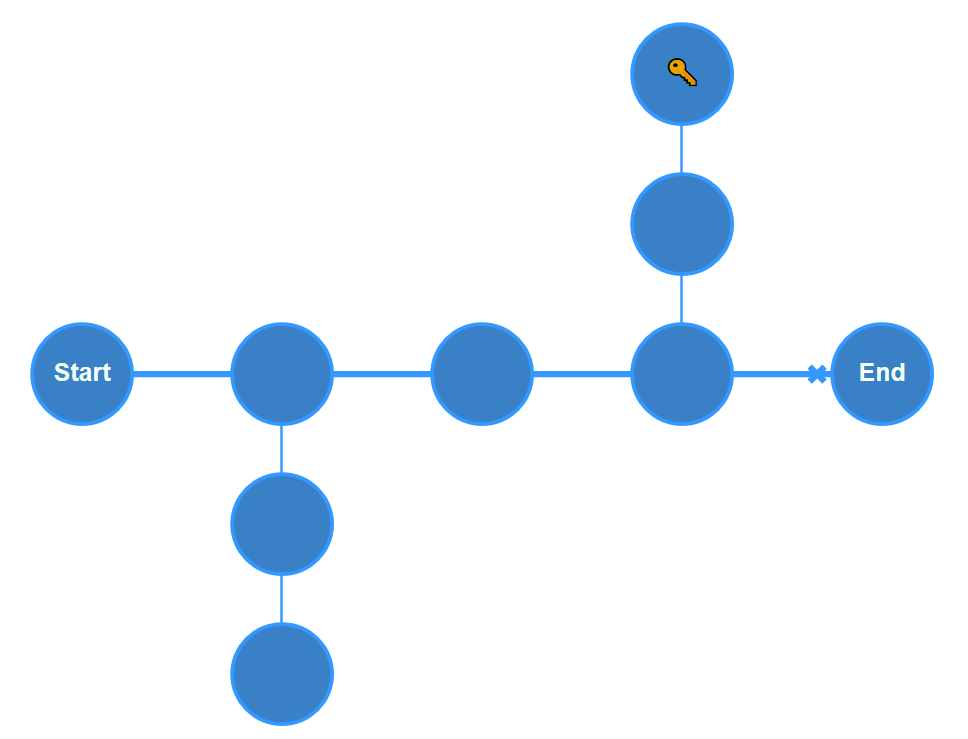

The path from the Starting Room to the Ending Room will be called the Critical Path. This is the shortest path that a player can take to complete the dungeon.

This is important, because it means that if the player needs something to complete the dungeon, then it means that the thing in question has to be on the Critical Path. It also means that there should not be a way to skip that thing. In this project, for now, we are going with the "linear structure, illusion of choices" approach.

Obstacles and keys

| Disclaimer: when I talk about obstacles and keys, those are figurative terms; the obstacle & key could be a locked door and a literal iron key, but it also could be a ravine and a ten-foot pole. Our goal is to stay as generic as possible. |

Another rule that we will need is for obstacles to appear before the associated key. We want the player to see the obstacle first, and then later find the right key.

Keys are forgettable. If the player finds the key before the obstacle, by the time they reach it, it’s not uncommon for them to have forgotten about it entirely. Think back: how many times have you, or witnessed someone, reach a locked door and couldn’t figure out how to open it? Then eventually tried every item, only to find out it was to be opened with the Magic Red Ruby that was obtained two hours ago?

On the other hand, obstacles are memorable. It’s a puzzle in itself; the player knows this obstacle leads somewhere, and they also know that they can’t open it with what they have at the moment. Instinctively, when we are presented with a puzzle with no apparent solution, our brain will put it on the back-burner while we do something else. Then, once we find the solution (the key), the association will be almost automatic, almost in a big “a-HA” moment. And we want that for the player; it’s a very satisfying moment that let them feel as if they just solved a puzzle that they were presented with.

So how do we do that?

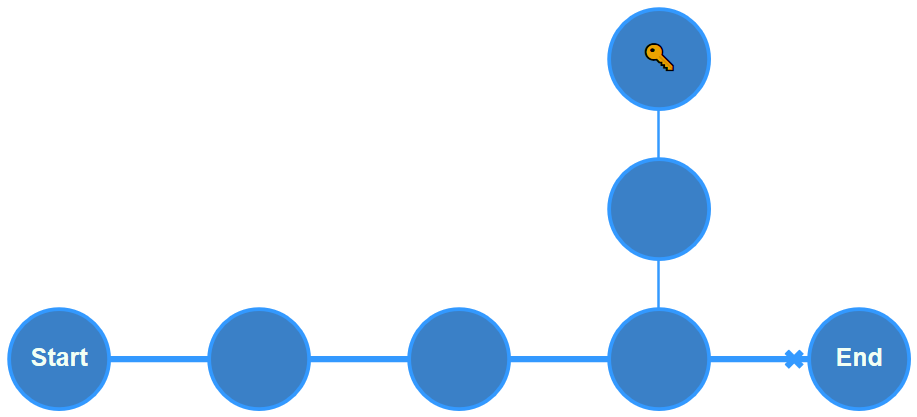

The answer is simple: every time we generate an obstacle, we also split the path with a Sub-path. That subpath will lead to the key necessary to pass the obstacle. The critical path, coupled with those Key subpaths, are the main structure of our dungeon.

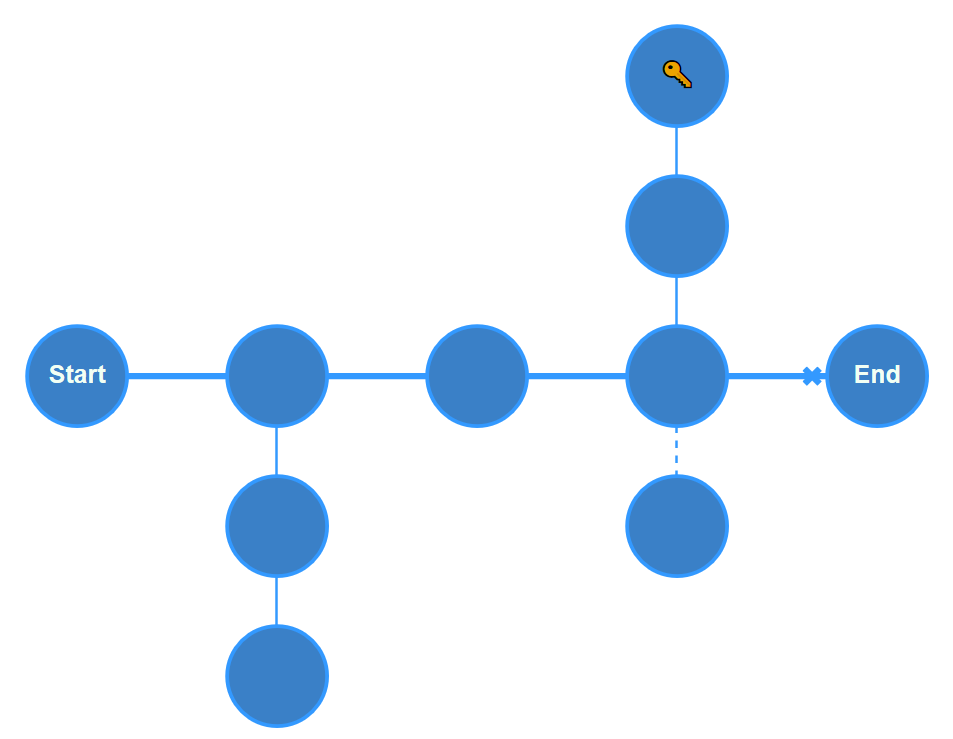

So this is nice, but it would be even better if we could get some optional paths in that dungeon. Stuff that isn’t necessary to complete the dungeon, but that will empower the Explorer and Looter types of player. So let’s do that, too.

Subpaths

Just like we grafted a Key subpath to the Critical Path, nothing prevents us from doing the same with just a normal subpath. The difference being that there is no key at the end of that path; there will have to be a reward though, because we are not mean to our players. Not that way at least. Going all the way down a path in a dungeon, only to find a dead-end with no reward whatsoever sucks. We’re here to make the player enjoy the dungeon. If you really want to be mean, however, that’s one rule you can ignore, I guess.

Now, another staple of dungeons is hidden passages. That’s pretty easy; it’s just a normal subpath but with the entrance hidden. The great thing about those is that the discovery of those passages is already an extra reward to the player, so that’s nice.

Sub-[...]-subpaths

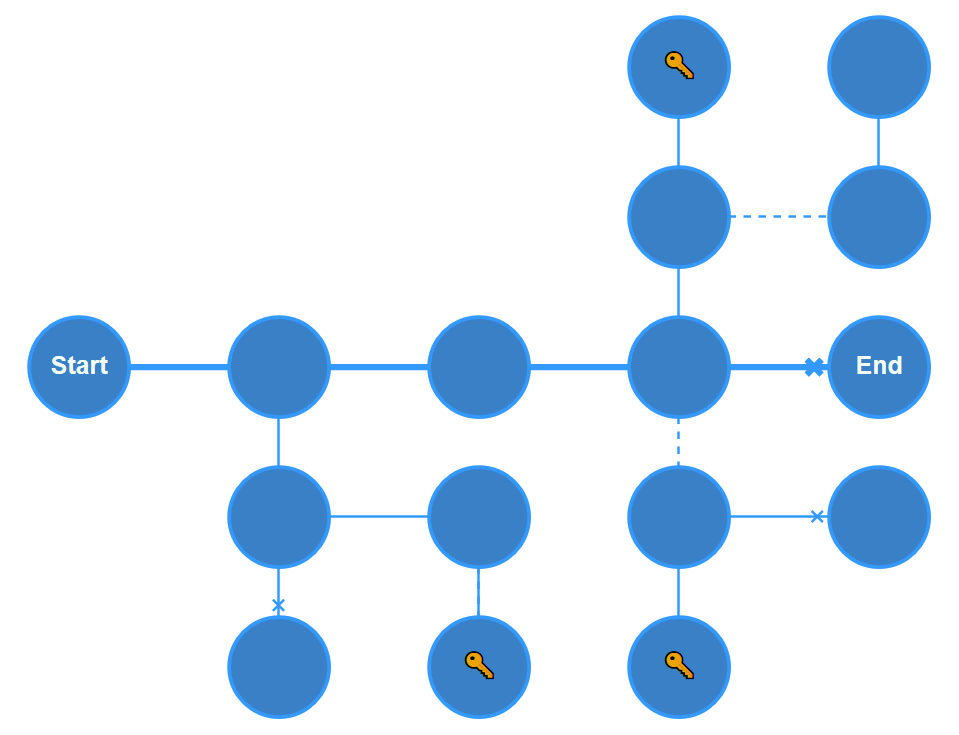

Now this is where things get really interesting. Technically speaking, a subpath is exactly like a path; it is basically a succession of rooms, and it has a starting room and an ending room.

So what’s keeping us from applying the same sub-pathing rules to a subpath itself? The answer is nothing. So we’ll do exactly that.

Potentially, this could go on forever, so we’ll mitigate this by keeping the branching chances pretty low, or maybe with thresholds.

Something else that I want to implement is detours. Basically the opposite of a shortcut (longcut?); a detour on a path is a room that is connected to two adjacent rooms on the path (note: it’s important that the rooms have to be adjacent; we don’t want to be able to skip any room on the critical path). Actually, it doesn’t have to be a room, it could be a succession of rooms. Like, say, a path. And like all paths, it can be subject to subpaths itself.

Final rules

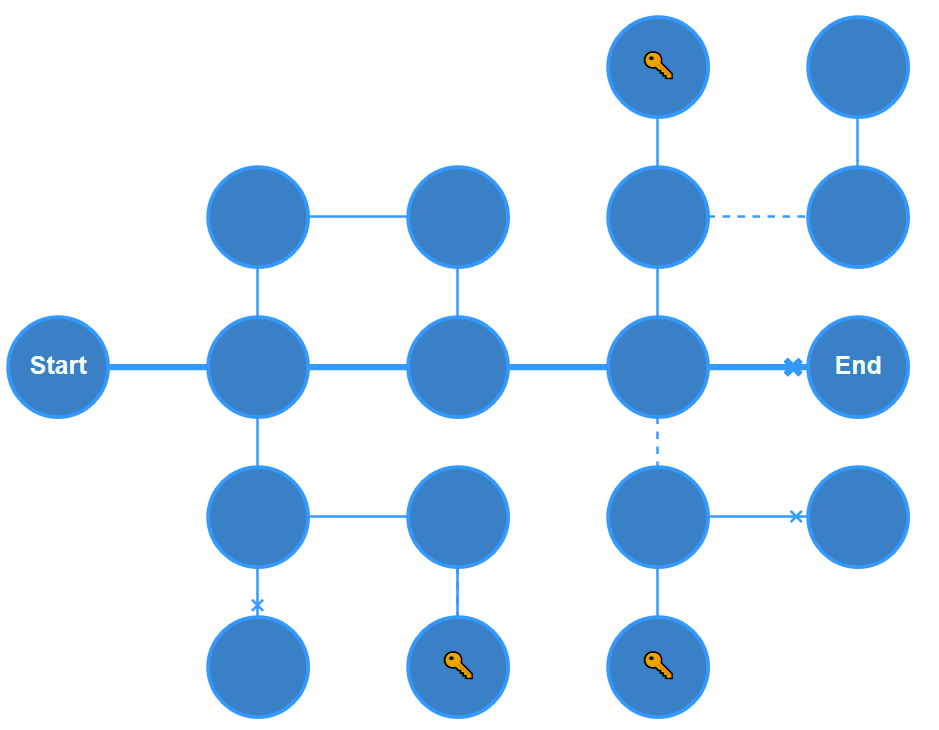

To resume:

- The main core of the dungeon is a succession of non-skippable rooms. It starts with the Starting Room, and ends with the Ending Room. We call this the critical path.

- Each room connection has a chance of being an obstacle, in which case it forces the creation of a subpath that leads to a key.

- Each room also has a chance of having a subpath. A subpath without a key at the end must have a reward at its end.

- A subpath is a succession of connected rooms. It can be subject to subpathing itself.

- A detour is a special kind of subpath whose Ending Room is the next room on the parent path. Like all paths, it is also subject to all kinds of subpathing.

So, what's next?

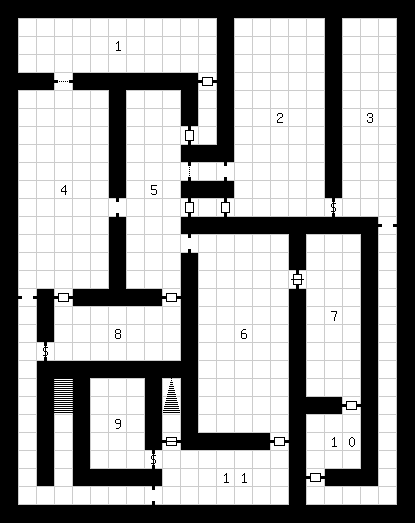

Currently, we have defined the basic rules for generating the paths of a dungeon. The next step will be to define rules for the actual geometrical mapping of those paths. Each node on those graphs represent a room; we now have to generate the rooms themselves in a coherent manner.

Also to note: I have represented those graphs in a very flat way; that was purely for readability. The rules that we will be defining later will decide the actual location of every room. And just like the rest, it will be procedurally generated.

Files

Get Sensible Dungeoner

Sensible Dungeoner

A tool for generating dungeon maps using tried-and-tested level design rules.

| Status | Released |

| Category | Tool |

| Authors | Duality Workshop, Linkyu |

| Tags | dungeon-generation, Procedural Generation |

| Languages | English |

Comments

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.

Well written and very interesting! This is a good starter's guide for creating dungeons even without the program.